News

Cancer, Evolution, and the Nature of Nature: Part 1

By Perry Marshall

June 15, 2021 | 0 Comment

When I was in high school, I was in the basement on a hot summer afternoon when I heard my dad arrive early from work. He walked through the door and broke sad news to my mom:

Betty, the cancer is back.

Two years earlier, he’d been diagnosed with cancer in his kidney. After surgery, the doctors said they’d nipped it in the bud. We breathed a sigh of relief.

But now the second time around I listened from the bottom of the stairs as my mom went to pieces. Mom became hysterical and was an emotional wreck for the next several months.

It didn’t take a genius to see that dad’s outlook was not rosy. Eventually he got

accepted into a special treatment program at Johns Hopkins in Bethesda Maryland. This brought three unexpected dramas for me.

The first drama was the fierce roller coaster of hope and despair that befalls cancer patients and their families. I battled depression my entire junior year of high school.

The second was that while my parents went to Bethesda, a college professor and his wife took me and my brother in for a month. Living with a different family and their two daughters was a remarkable growing-up experience.

My dad was a minister, and the third surprise was that our faith community sent out a secret fundraising letter: “Bob has never been to the west coast and he has terminal cancer. If you’d like to send Bob, Betty and the family on a special vacation, contribute and let’s help them enjoy their final days together in a memorable way.”

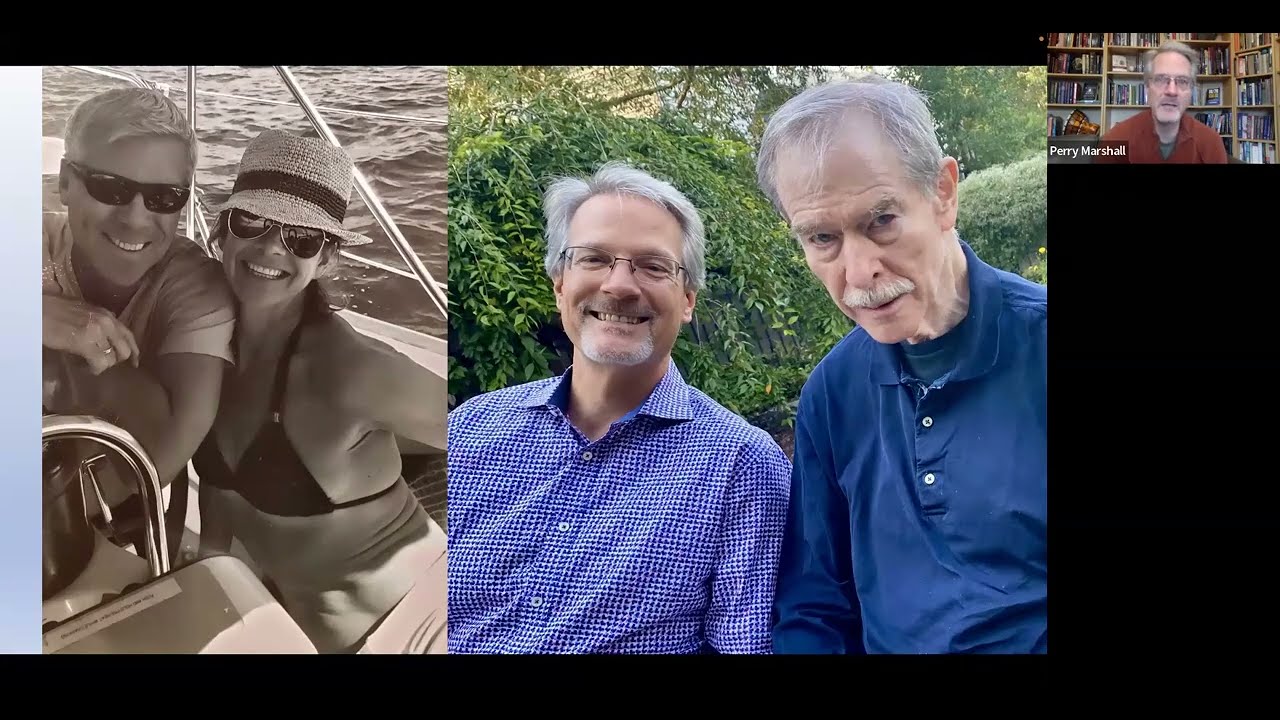

They broke the news to my parents on a Sunday night. $11,000 had come in and someone loaned their luxury van. To us, this was a princely sum of money. There was not a dry eye in the place. Their generosity funded a 5-week tour of every state west of Nebraska – including Alaska and Hawaii. I had never been west of Colorado so this was special indeed. We took the photo above on that vacation.

During our trip, we had ample time to process and plan for “life after dad.” The vistas of Alaska and the painted deserts of New Mexico were breathtaking, but our days were punctuated with reminders that dad was slipping away. He took painkillers on regular intervals, with rising discomfort as the most recent dose would fade. Bedtime triggered coughing that often lasted an hour before he fell asleep.

His treatments at Johns Hopkins, sophisticated though they were, did not succeed. The cancer spread and his voice became hoarse. Three months after our vacation, he passed.

Having first lost dad when I was 17, then witnessing numerous friends and mentors being taken away by cancer; now having organized a symposium on Cancer & Evolution with some of the world’s most respected scientists… I can’t help but ask:

Are cancer cells flat out smarter than any oncologist or scientist? Or is this just an illusion, a story that we tell ourselves?

Answer: I don’t believe cancer cells appear to be smart or simply act as though they are smart. I believe cancer cells are smart. To a startling degree.

But “smart” is a category that mainstream science doesn’t know what to do with. In fact a large part of the profession has been in denial of this for 100 years. The field has evolved an entire terminology to evade the purposiveness of life… all the way down to the dictum that every scientific paper should be written in passive voice (which makes for a lot of dreadful reading).

But far worse, it obscures cause and effect.

As a result, research is beset by what appears to be a thicket of seemingly unrelated questions, cancer being one of many. Some people even define cancer itself as “100 different diseases, all under the same name.” But I believe a whole range of science’s deepest mysteries are all the same question – the question of purpose.

The technical term for this is “agency” – the capacity to act with intent. The very question that materialistic science has tried to avoid for a century.

My new paper in Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology offers a mathematical proof that accounts for this 100 year impasse in science, and how we can escape from it – while unifying six major scientific questions under a single framework. All are Big Questions.

When I say proof, I use the word in the formal mathematical sense – which is an important detail. Science can only disprove; mathematics proves, using pure logic.

As I say in the paper:

“If it can be proven that information or mathematics itself cannot be reduced to computation, then such a proof would shake the very foundations of science itself. It would mean that science’s goal of defining rules for everything is impossible. This paper provides such a proof.”

In Part 2 I’ll explain why, far from being some philosophical or academic abstraction, this offers a completely different way of viewing our familiar world, and engineering new solutions to old dilemmas.

This discovery is key to very practical problems… like our medical profession’s failure so far to find a cure for cancer.